“To really understand the Ajax debacle, you need to go back decades. Officially known as an armoured reconnaissance vehicle, Ajax is a replacement for Scimitar, a smaller, lighter tank, which entered service in 1971, and whose armour, crew protection, and firepower was looking outdated as long ago as the Desert Storm campaign of 1991. As a result, in the decades since then, a succession of replacements were commissioned, then abandoned, as the certainties of Cold War land warfare gave way to asymmetric conflicts against insurgent foes, and the emerging promise of new digital technologies outshone the more prosaic allure of armour.

‘After the Cold War the Army struggled to know what role it should play and what kit it should have,’ says Trevor Taylor, a procurement expert at the Royal United Services Institute.

The Scimitar succession started in 1992 with Tracer – the Tactical Reconnaissance Armoured Combat Equipment Requirement, junked nine years later. That was followed by the Future Rapid Effects System (Fres), a huge order for 3,000 armoured vehicles covering 16 battlefield roles, which was cancelled in 2008 – the same year the first Fres vehicle was supposed to enter service, at which point officials conceded they were still at least seven years from doing so.

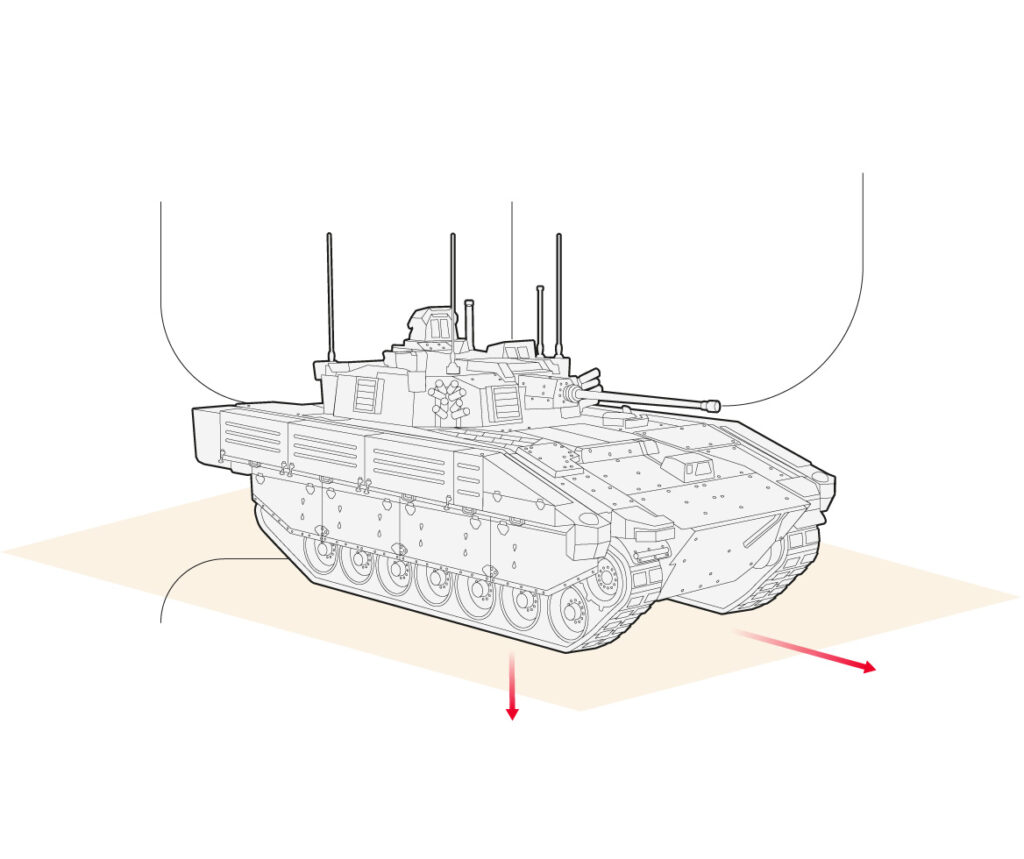

In July 2010, the MoD signed a contract with the American manufacturer General Dynamics, for what was to become known as Ajax, whose combination of firepower, manoeuvrability and armour would make it a step change from Scimitar. But Ajax has suffered the same fate as its predecessors. Manufactured in Wales, it was meant to enter service in 2017; its deadline was soon put back to 2020 as specifications changed. In 2019, in anticipation of its delivery, the Household Cavalry, which will be using Ajax, moved the regiment permanently from its urban location in Windsor to Salisbury Plain to accommodate the heft of the tanks. As yet, they are yet to materialise.

Now there is talk of 2025, but in reality no one knows for sure if Ajax will ever see a battlefield at all. Rather, it has become the latest casualty in a record that, for almost a quarter of a century to 2020, saw not a single new armoured vehicle from the core procurement programme enter operational service with the Army. How has it all gone so wrong for so long? And what has gone wrong with Ajax in particular?

When it comes to Ajax, says Taylor, the very chronology of disaster that preceded it was in itself a major problem. ‘The last 25 years have been a succession of procurement attempts abandoned for something else. So at the MoD that makes you determined to make Ajax happen – and in a hurry.’ :”

Comment: The same kind of thing has gone on this slide of the pond. The GWOT confused ground forces leadership and paralyzed acquisition thinking until recently. This was complicated by anti-Army leaders like Rumsfeld, who never escaped his youthful experience as a naval aviator.

It is very easy to screw such R&D and procurement processes up. When I was a student at the War College, I had a LTC classmate who was probably the most Type A man in the class. He was a frightening creature, consumed by ambition. He was directed by the medical staff to study me, the most Type B person in the class and how I acted. He would ask me thigs like, “what are you doing?” The answer to this was something like “thinking.” or “how did you get here?” Answer, “beats me. I didn’t pick me.” Or “why do you wear a watch?” Answer, “You expect me to do so and I don’t want to miss appointments.”

This poor man had been the working level project officer for something called the “Sgt York division anti-aircraft gun.” It was a great idea, a mobile radar turret driven two barreled Bofors mounted on an obsolete tank chassis. Great idea.

Trouble was that prototypes couldn’t hit a damned thing, and no matter how much they fiddled with it, it still couldn’t hit anything in the air.

A lot of money had been put into the project, and this guy was kicked to the curb as the failure became evident. They let him stay on long enough to get enough time to retire. pl

Inside Britain’s £5.5 billion military disaster (telegraph.co.uk)

Same thing happened on a greater scale with the Future Combat System (FCS ). $32 billion spent with nothing to show for it. Or maybe just the biggest chunk of the $32B, which had been forked over to industry for the Manned Ground Vehicles or MGV portion of FCS. The intent was to replace the M1 Abrams tanks, M2/3 Bradleys, & M109 SP howitzers with lightweight (less than 19 tons) counterparts. It was a disaster. Stop work was finally ordered in 2009.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Future_Combat_Systems_Manned_Ground_Vehicles

The other Services have had their debacles also. I’ve thought for a long time that all the Services should adopt a primary career path for acquisition officers. The AF does it and I believe they have gotten good results from it. They actively recruit young college grads with BS or MS in Aeronautical or Electronics Engineering, etc. They make Program Management gurus out of them and set them loose to get the defense industry to toe the line. These guys are full time acquisition officers for their entire career and NOT part timers from a different career path (they are sometimes not so affectionately called ‘tourists’). And yes I know the AF has also had some program failures (especially in software), but IMO those can be laid at the feet of shifting system changes or ‘requirements drift’ forced by top-level AF leadership.

First time I have read one of your articles. Great job! I was in the British Army for 34 years and my first civilian job on leaving was in our procurement organisation. I recognise quite a few of those problems. Military officers serve there for only 2 years and mostly have little to zero experience of Defence Industry.

The US Navy has currently rather independent acquisition communities. At one time we had a Naval Material Command but it was deemed redundant. That has been replaced by Assistant Naval Secretary for RD&A (vacant, but DoD head of DOT&E has been nominated last month by the administration).

DoD acquisition is largely process driven, with “milestone” attainment the primary focus, most intensely in ACAT 1 programs that are subject to congressional oversight.

I don’t know that there is a magic formula for ensuring successful acquisition. Certainly within the Special Projects (SP) program (USN strategic missiles), there is closed-loop detailing within the Engineering Duty community and that has some advantages. But when you look at Naval Reactors, that has always been a mix of specialists and operating nuclear engineer unrestricted line officers. Same with Aegis. But all these programs have had in their history talented and successful key leaders who set the tone for how the program was managed. I don’t know how you identify these key leaders as junior officers for grooming.

My personal background as a naval officer restricted to engineering duty included significant time in the Tomahawk program, which had numerous failures until an admiral was assigned who set things straight. My personal view is that the amalgamation of operating engineers (Engineer Corps) into the line with a breaking out of a subset restricted to engineering duty at the turn of the 20th century was not helpful, nor elimination of the Constructor Corps 40 years later.

Congress directed DoD to create a managed acquisition community with certain jobs restricted to those in acquisition professional community. Defense Acquisition U is the mother-ship for the community. (Not a grad myself, but my better-half is, and she was also a major program manager.)

As far as contractor management, that has largely been migrated to the DoD (DCMA) . We still have naval Supervisors of Shipbuilding (SUPSHIPS) but I don’t think they are nearly as involved as in the past. (Of course, we also used to construct ships in the public shipyards, but those days are long gone along with the hands-on expertise.)

Let’s not forget the great ‘green’ navy that launched the LCS class of ships that can neither run nor fight, now being decommissioned. The Ford class carrier (CVN 78) that has more experimental crap on it that is only now being deployed. It had a bunch of waivers in the construction program, too:

“Prior to the [Ford] acceptance trials, the CNO also approved a waiver for the advanced arresting gear that excluded the system from inspection during the trials.”

https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-22-104655.pdf

18 trial waivers and 36 delivery waivers. You can’t get a car delivered to you with that many exceptions to final build quality, but this is the navy, so….

Here’s a site with a great deal of navy specific commentary that provides some parallels to the discussions here.

https://navy-matters.blogspot.com/2022/09/a-baby-step-in-right-direction.html