One of my pre-occupations is the cycle of novels that I wrote concerned with what I think I learned in life. It is set in the American Civil War and called “Strike the Tent.” Why? If I knew why perhaps I could have set it in some other time and place. I have been writing at this for a long time. In one of the books, there is the story of a French professional soldier (John Balthazar), an officer with much service in Africa, who is sent to America to “observe” Lee’s army for his government. Once here, he becomes ever more involved until he ends by being asked to form a provisional battalion of infantry from men nobody else knows what to do with. Line crossers, men from broken units, disciplinary problems, etc. He sets out to do that. In this passage we see his battalion going into Winter Quarters in November, 1863 south of Culpeper. Virginia. They have just made a long withdrawal to the south, away from the disastrous field of Rapahannock Station. Pat Lang

———————————-

“Throughout the army, soldiers started to construct their winter quarters. They had lived so long in the forest that they could build solid little houses of sticks and mud if they had a couple of weeks in which to work. Small towns arose in the woods. They filled up the forests that sloped away to the northwest from the foot of Pony Mountain. Smoke drifted in the wind, eddying and streaming, bringing an acrid bite of wood taste in the air. Oak and hickory, maple and poplar, the smoke brought the smell of their little communities so like those their ancestors had made in the beginning of their new life in America. The men thought of Thanksgiving; some reached out beyond that to remember Christmas. Balthazar watched his troops build their winter town. He had never seen soldiers do such a thing. In Europe, soldiers on campaign lived under canvas or in requisitioned houses. He thought their skill a marvelous thing, and told them so.

On the 26th they had Thanksgiving. Smoot and Harris explained the nature of this feast to Balthazar, telling him of the memory of God’s providence to the colonists at Jamestown. He heard them out, and sent hunting parties into the woodland.

Jubal Early came to dinner. He sat on a saw horse in the barn where they ate, a tin plate of venison and wild turkey in one hand, a tea cup of whiskey beside him.

The troops sat in the hay eating happily.

Balthazar had taken charge of the cooking, supervising the half dozen Black cooks that Harris recruited in Hays’ brigade. The day the cooking started, Harris was pleased to have several men volunteer to help. Among them was Smith, the “D” Company commander. After watching his creation of an admirable kettle of turkey soup, Balthazar was sure that Smith, like Harris, was professionally trained.

Early complimented them on the stuffing, and said he had never had anything quite like it. He accepted a second helping. He had a chaplain with him, a French Jesuit who worked in the military hospitals in Lynchburg.

The priest and Balthazar chatted in their own language during dinner. The men listened to this with interest, turning from one to the other, examining their commander, seeking assurance of something they could not name.

After dinner, the priest offered his thoughts on the meaning of such a remembrance in wartime and the injustice of the war being waged against them by the North.

The soldiers listened politely.

When the chaplain finished his talk, Early stood up and announced that General Ewell was gone on sick leave for his old wound, and that he would be in command of Second Corps until Ewell came back. He said that they would be attached for now to corps headquarters.

You could see from the soldiers’ faces that they were not sure if that was good or bad.

The priest offered to say Mass if there were Catholics present. A number raised their hands and he moved off to a corner of the barn with them. Balthazar asked Early if he wished to attend the service. After a moment’s thought, the general shrugged and said he could not see any reason not to do so. “After all,” he said, “the Pope has taken note of us.” After Mass, the Jesuit asked if Balthazar wished him to hear his confession. The answer was no.

A courier came at four o’clock the next morning with the news that Meade was across the Rapidan, and marching southeast through the Wilderness.

Balthazar had found among his men a soldier who had been a bugler in a regular U.S. cavalry regiment. “Reveille” sounded sweet and compelling in the darkness of the camp.”

Pat Lang

———————————-

Comment: Colonel Lang first posted this in 2012, I believe. At that time I commented as follows:

The Thanksgiving meal is a special occasion in the Army as all us old soldiers know. It is a time when us officers donned our dress whites (at least in the 25th Infantry Division) and spent time with the troops in the mess hall.

Stafford was the winter quarters of the Union Army that Lee bloodied at Fredericksburg in 1862. There were more Union troops in Stafford that winter than there are Stafford residents today. The small soldier towns that so amazed Balthazar also sprang up in Stafford although the inhabitants wore blue rather than butternut and grey. These soldier towns are depicted in our White Oak Civil War Museum and our new Civil War Park.

A lot has changed since 2012. Most importantly we lost Colonel Lang. We did not develop a friendship until comparatively recently. We never crossed paths professionally although we trod many the same paths in our lives and careers. I miss our conversations and I miss him. Thankfully, we have his writings, his wisdom and his blog to remind us of him.

Our Civil War Park is still going strong. It’s not anything spectacular, not the Gettysburg battlefield, but it’s well done and chronicles an important period in local history. I still enjoy the occasional visit. We no longer have our White Oak Civil War Museum with the death of D.P. Newton, the founder and curator of this wonderful little museum a little over four years ago. The man was a tireless relic hunter and Civil War historian. I’m sure he and Colonel Lang would have hit it off very well. Thankfully, most of his collection is now in a dedicated museum under the care of Jon Hickox, himself a lifelong relic hunter, the president and owner of The Winery at Bull Run in Centreville. A lot of the documents and maps in D.P. Newton’s collection are now in the Virginia Museum of History & Culture in Richmond.

As a final note, I always referred to Colonel Lang as Colonel Lang on this blog. When we talked, it was Pat. That’s a military tradition just like donning my dress whites and serving Thanksgiving dinner to the troops in the mess hall all those years ago.

TTG

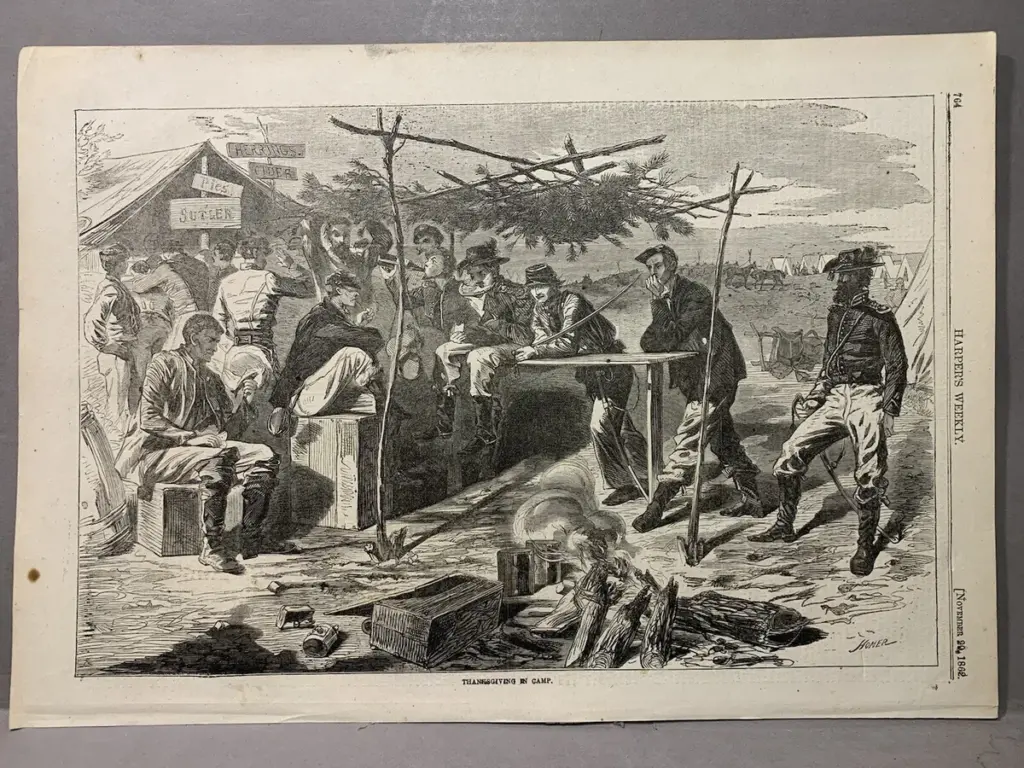

Those are Yankees I believe. Winslow Homer the painter only traveled with the Union Army. A shame they had to buy meals from that sutler tent on their meager pay. But government rations back then were notorious for rancid meat. But still, it had to be better than what Jeff Davis’s troops were eating.

My Thanksgiving in the field was white bread cold turkey sandwiches flown in to our LZ on Que Son mountain. No mayo, no mustard. The onions were good though, we ate them like apples, must have been Maui sweets.

A most evocative writer and a vast fund of knowledge to draw on. Wish he’d written more.

The Colonel was also a sharp observer of the political scene. He did mention that he had a collection of his papers to be published at a later time. Presumably they would expand on the subject matter of “Tattoo”. If so, they would give a picture that would take us from the Vietnam war and before right up to nearly the present day.

They would also show the journey he himself made. I was put onto SST late, by an Australian friend in 2015 who said I was missing something significant coming out of the States. I had been, and I scoured the back issues eagerly to see what I’d been missing. A lot. My impression was that they showed that journey. It sounds contentious, but I saw it as a journey towards an ever increasing repudiation of what we, not only in the States but in the West generally, now accept as normal or at least unavoidable.

He took his fellow pilgrims along that journey with him. This latecomer pilgrim tagged along on the edges of that pilgrimage. It would be good to have a deeper insight into that journey. Is there an intention of assembling and publishing those papers?