In the modern era, the proa cause was first taken up by multihull designer Dick Newick, who in 1967 designed CHEERS, a 36-footer he called the “Atlantic proa.”Unlike a traditional Pacific proa, which always keeps the ama on the windward side, the Atlantic proa has the outrigger on the leeward side. With Tom Follett at the helm, CHEERS won third place in the 1968 Observer Singlehanded Trans-atlantic Race (OSTAR), becoming the first American boat to complete the race.

The potential of the type was spotted by the British yachtsman and mustard millionaire Timothy Colman, who set a world sailing speed record of 26.3 knots with his 56′ proa CROSSBOW in 1972. He topped that three years later, clocking 31.2 knots, and went even faster in 1980 with his hybrid proa-catamaran, CROSS-BOW II, this time bringing the record up to 36 knots. Since then, proas have consistently claimed world sailing speed records (when not challenged by wind-surfers and kite surfers), the most recent being the carbon-fiber proa SAILROCKET 2, which Paul Larsen sailed to a record of 65.45 knots in 2012. One of the biggest names in the proa world is Russell Brown of Port Townsend, Washington, the son of cruising-multihull pioneer Jim Brown of Virginia. The younger Brown built the 36′ JZERRO, which weighs just 3,200 lbs and is capable of 22 knots, and sailed her across the Pacific from San Francisco to New Zealand in 2000. More recently, JZERRO was acquired by Ryan Finn of New Orleans, who in 2022 sailed her singlehanded 13,500 miles from New York to San Francisco, making her the smallest craft to accomplish that feat.

Despite these remarkable achievements, there is still a pervasive view that proas aren’t viable sailing boats. “It has been said that the multihull community is the lunatic fringe of the sailing community, and the proa community is the lunatic fringe of the multihull community,” according to proa enthusiast Simon Penny, a polymath theorist and teacher with a keen interest in Pacific cultures (see www.simonpenny.net). Yet the most common reason quoted for building a proa is getting the most bang for the buck. There’s simply no other boat that will sail so fast at so little cost.

https://www.woodenboat.com/sites/default/files/issue/WB298-TOC.pdf

Comment: This was an interesting article on proas in general and on one man’s adventure in building and sailing his proa. It’s the story of Willian Lewis, a Brit with a life long interest in wooden boats. He took two courses in sailing at the Wooden Boat School while his sons were attending college in the States and eventually signed up for a 40-week boatbuilding course at the Lyme Regis Boat Building Academy and Furniture School in Dorset, England. Being the oldest guy in the class, everyone expected him to choose a traditional sailing craft to build. Instead, the once sensible corporate lawyer threw caution to the wind and chose to build a shunting proa. He chose the Gary Dierking designed T2. He and his class built the boat. He christened her TINY GIANT and then learned how to sail her.

The entire article is well written in the standard Wooden Boat style. If you’re not a subscriber, you may not be able to reach it on the intertubes. If not, it’s worth your time to see if your local library has a copy. If you can’t easily get to it, here’s another passage covering what Willian learned about sailing his proa.

William told me he had had the boat out in winds of 20 knots or more. “She’s not as fast as a planing dinghy but faster than a normal 30′ cruising yacht. She has quite a big wetted-surface area, so it takes a bit of wind to unstick her, but she comes alive with 10 knots and will get up to 9 knots quite easily.” Winds of over 20 knots brought serious problems: “The sail’s tack started thrashing around wildly and bashing the hull and me when I tried to sort it out. That’s why it’s important to have the halyard handy, so you can dump the sail in an emergency.”

In many ways, trimming the sail is like trimming a gaff-rigged one: you need to ease the sheets and can’t expect to sail too close to the wind. With the wind forward of the beam and the sail set to get the center of effort in just the right place, she should sail herself in a straight line, though William and I didn’t quite achieve that on our trial run. The sail trim can also be adjusted by raking the mast to leeward to produce a better sail shape in light airs or to windward in a strong blow, like a windsurfer sail. Getting even more fancy, the windward brailing line can be tightened to give the sail a fuller shape, like using the “tunnel effect” on a lateen rig (see WB No. 270), although William says he hasn’t reached that level of prowess yet.

Steering with a paddle takes quite a bit of getting used to. William made it look easy, but I struggled with it, especially off the wind. As one sailor, Chris Grill, who sailed his extended T2 DESESPERADO from Mexico to Panama in 2011–12, wrote in his blog (grillabongquixotic.wordpress.com): “My dream is to steer with one foot whilst playing the fiddle and drinking gin-and-tonics, and steering oars are incompatible with that ideal.” Grill eventually fitted dual rudders, one at each end so one could be raised and the other lowered depending on the direction of the shunt.

One of the biggest challenges William has faced is getting the boat on and off its mooring. One thing you must avoid with a proa is allowing the sail to be taken aback, so heading into the wind to pick up a mooring simply isn’t an option. Instead, William usually drops the sail when he’s close enough to paddle the rest of the way if necessary, which is easier said than done when the river current is running at 4 knots, as it sometimes does in this section of the River Dart. Good sculling skills are an essential part of sailing a proa.

William was also planning to fit a stronger shunting rail, a strip of wood on the leeward side of the vaka that ensures the yard runs smoothly while shunting, to control the tack more effectively in strong winds. He is also going to fit a block-and-tackle to hold the aka more tightly into the ama and prevent it from coming loose. While some independent movement of the ama is desirable, too much play could damage the boat.

TTG

Local library carries Wooden Boat. But regrettably that issue is missing. Some local sea rat must have ripped it off.

Wingapo! Netah TeeTeeGee

Thanks for TX’ing another small boat article, so refreshing these days where worldwide discontent is rife and appears uncontainable. Then, of course, is your upcoming abominable election. It’s taking up more news here in NZ than our own parliamentary election that we had last year!

I’m a great fan of small boats and have been since my childhood. Getting nearly drowned on many occasions has shaped my adulthood in ways that fear of death has become somewhat diminished. Then there is exhilaration of flying along at high speed, sightless due to spray and nearly out of control. That helps.

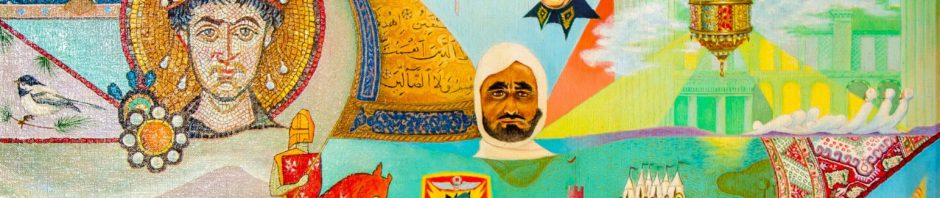

Its good to see proa as a developing class as you detail. One main advantage of Proa is potential high speed. The early Pacificians explored the entire pacific, west to east, from Taiwan to Rapa Nui (at least) and as far south as Enderby Island (-50.5 E, 166.3 S) in the roaring forties. High speed, good pointing and the ability to carry cargo, including settlers, was a big plus. In the 10th to 12th century, the Pacific proas were the highest speed ships in the world whereas the caravels and carracks of a similar and later period were slow and cumbersome but these could carry more cargo.

It’s a great myth that the early pacific sailors wandered aimlessly around the Pacific Ocean looking for new home. Their boat building, sailing and navigation skills were so good they could return to base easily. Tales of fascinating new territories would attract new captains and crews eager to voyage into the beyond.

My small boat days are over, but never-say-never. Skills obtained over a lifetime only slightly diminish. I’m more comfortable chartering a large boat, suitable for family and friends in some distant land that none of us have never been to. Note: by choice, these boats will be monohulls no less than 14m.

Whiriwhiria to Rangatira kia tupato

rob

Labas Rob,

My interest in proas was sparked not by proas, but a rainbow sailed Hobie cat just off the Waikiki beach. It was flitting across the water instantly reacting to the slightest puff. It was like those water skipper bugs gliding over the surface of a pond. Not long after that, I came across the Hokulea tied up not far from that spot. It wasn’t long after her capsize off Moloka‘i and the loss of Eddie Aikau. I sensed a recent tragedy before I knew the full story. From that point I dug into everything Hokulea and Polynesian sailing.

I’m happy with my sailing kayak and will probably get back into my windsurfer, but maybe a little shunting proa is in my future.