Translated by Steven J. Willett

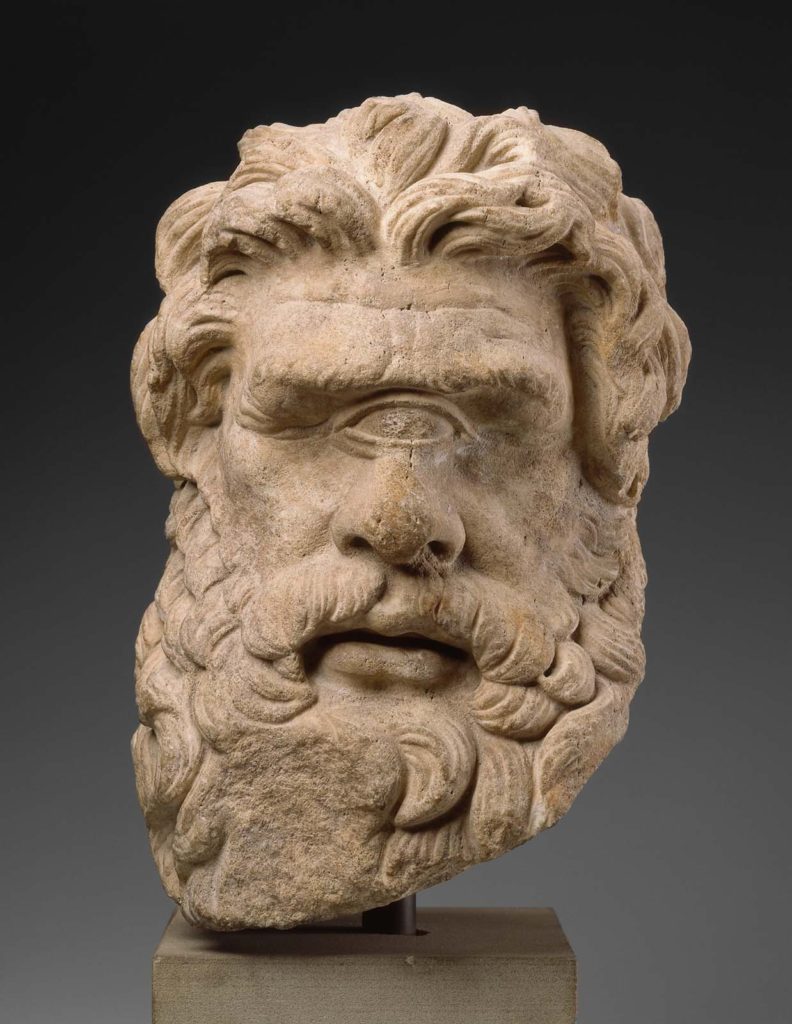

This is the head of Polyphemus, either Greek or Roman, Hellenistic or Imperial period, c.150BC or later

Note: The singers in the contest are Daphnis the herdsman and Damoetas, whom we do not encounter anywhere else in Theocritus. The poem is addressed to Aratus, who also appears in VII.98ff as a friend of ‘Simichidas,’ the narrator of VII. The identification of this man with the famous poet Aratus is possible but cannot be proven. The theme of both songs is the love-affaire between the Cyclops Polyphemus and the Nereid Galatea, and this topic also appears in XI.

Theocritus was born c.300BC in Syracuse, Sicily, and died sometime after 260BC. He was the creator of pastoral poetry, some of which were termed Idylls or Εἰδύλλια. It’s clear that two early collections of his work were assembled, one of doubtful authorship that formed the corpus of bucolic poetry, and one of strict authorial composition by Theocritus.

Damoetas and Daphnis the goatherd once to the same place

gathered, Aratus, the herd together. One of them had a chin

golden, while the other a beard half-grown; and at a spring both

seating themselves in midday summer thus did they sing.

First began Daphnis, since he had first challenged the match.

Daphnis

She surely, Polyphemus, pelts the flock your own Galatea

with apples, calling you “Stone-hearted lover and goatherd.”

And you don’t look at her, wretched fool, but are seated

sweetly piping. But once again, look, she pelts the dog

that follows you as sentry for the sheep; and it barks

looking at the sea, and the beautiful waves reflect it

in bounding along the gently splashing seashore.

Watch out it does not spring upon the maiden’s legs

as she emerges from the sea and tear her lovely skin.

And from there she pampers herself; as from thorns

the dry thistledown, when the fair summer parches it,

she flees the lover and pursues after the non-lover,

and moves the stone from a sacred line; for truly in love

many a time, o Polyphemus, things foul have seemed fair.

Then Damoetas raised his voice and began to sing.

Damoetas

I saw, by Pan, when she was pelting over the flock,

she didn’t escape me, not by my one sweet eye, and with it

may I see to the end (let seer Telemus who declared the bane

carry the bane home, and keep it for his children);

but I myself to tease her back am not going to stare,

but tell her that I have another woman; and hearing that

she’s jealous, O Pan, and wastes away, and from the sea

she’s frantic searching all around for my caves and flocks.

And I hissed at the dog to bark at her; for when I loved her,

he whimpered after settling his muzzle on her lap.

And perhaps, seeing me do these things, she’ll often send

a messenger. But I shall bar the door, until she swear

to spread for me the lovely bedding on this island;

for certainly I don’t have a foul shape as they tell me.

For lately I gazed into the sea, and it was serene,

and fair was the beard, and fair my single eye

as judged by me, and clearly showed, that my teeth

reflected a whiter sunbeam than Parian marble.

And to avoid an evil boast, I spat thrice on my breast;

for the old hag Cotyttaris had taught this to me.

Saying such great things, Damoetas kissed Daphnis

and gave him a pipe, and Daphnis a fair flute to him.

Damoetas played the flute, and herdsman Daphnis piped;

the calves then straightway danced about the soft grass.

Neither won a victory, but invincible were they both.

Will you please tell us more why you chose the translation of “hag” for the description of Cotyttaris? I see her also described as an old woman or a witch. What was the lineage of the original word that made “hag” your own choice?

Women of a certain age do have an interest in “aging female” descriptions over the ages – from the middle age crone also being called a “hag”, to later interpretations today as now a wise woman, the Hestia model.

I am a fan of Jean Shinoda Bolen – The Goddesses in Every Woman -exploring psychological verities expressed in Greek mythology that can still apply today. Pop psychology or not, I personally have found her insights very helpful.

Thanks. (Please accept this as genuine question out of curiosity and not a launching pad into a feminist rant. Not my thing as I hope you by now know.

γραία as a noun refers to an old woman, but used as an adjective it means old, withered, haggard. It was used to describe the Eumenides in Aeschylus. A. S. F. Gow in his two-volume critical edition of Theocritus translates VI.40 with ‘hag,’ II.91 with ‘hag,’ and VII.126 with ‘crone.’

Next question: any indication what age was considered old enough to warrant a “hag” description.

Any “birthing person” (ha ha) who was now past child bearing age, or a “withered” four score and seven years?

Deap

Too auto-biographic and self-pitying a comment.