“… A mile away, across the grassy valley from the cemetery ridge, Pickett’s Division lay waiting in the woods. They had come up to this position in the early morning hours. The officers occupied themselves with the usual business of placing the long lines of men in the order in which they would attack.

After that, the men lay down, pretended to sleep, or devoted themselves to the routine of preparation for a major action. They cleaned weapons, wrote letters, talked to their messmates and made final judgments on the comrades with whom they would go forward against the guns.

Jepson Thacker lay on his back looking up through the leaves and branches of a patriarchal and seasoned oak. He had the thick trunk of the tree between him and the Yankee guns. The smell of leaf mold and wood smoke hung in the air. He tried to keep his mind on the beauty of the forest scene through the long wait under fire. The 7th Virginia Infantry Regiment was all around him, stretching out to either side of his company. The company had stood the artillery fire well. Cannon balls had caromed through the trees for the last hour. From time to time one killed or maimed, but for the most part the soldiers simply stepped out of their path. The shrapnel from air bursts in the tree tops was a more serious matter. They had lost several men to shell fragments.

In the midst of it all, “Pete” Longstreet rode into view, going down the line, slowly passing them by on a tall black horse, looking at them with an odd, pale expression on his usually ruddy features. The black horse shied from the sounds of falling leaves and branches ripped off trees by passing solid shot. A sergeant in Thacker’s regiment stood up to yell at Longstreet. “You damn fool! Do you think we need you to do this to make us fight? Get the hell out of here before you get killed!” Longstreet bowed his head to the man, and rode on.

When the barrage stopped, Thacker sat up and looked for his company commander. The captain stood fifty feet away talking to an officer from another company. Thacker just caught the end of their talk. “Oh! Here we go!” the other officer said. “Please do remember me to your cousin Sally! I haven’t seen her since before the war..”

The captain walked back. “Get ’em up Jepson,” he said. “I expect we’ll be leavin’ now..”

The regiment formed and dressed its ranks. Thacker saw General Kemper and his staff take their place in front of the center of the brigade line. This happened to be exactly in front of Thacker’s company.

“Watch Morrison and Davidson,” the captain said in a soft voice beside him. “I’m takin’ everybody in today, everybody. If they drop out, kill ’em.”

Thacker nodded. He checked his revolver to make sure none of the explosive metal priming caps had somehow been lost.

Claude came up the hill to stand beside his brother on the ridge just as the Rebel infantry began to emerge from the distant woods. He intended to remonstrate with Patrick against their presence, but the scene before them silenced him. “My God.. My God,” was all he could manage. There was at least a mile of troops forming in front of the wood line across the valley. In the center of the line lay a triangular projection of forest. To left and right of this feature regiment upon regiment of the familiar motley brown figures moved into position, coming out of the trees and halting behind their leaders and flags. Somewhere, a band began to play.

From his post behind the company’s two ranks, Sergeant Thacker looked up and saw the mile of open, gently rolling ground for the first time. He had been busy correcting the alignment when they first emerged into the sunshine. Now he saw it.. It looked like the surface of a dinner plate. The far lip of the plate was a low ridge with a small patch of trees in the middle. Union artillery and infantry covered the ridge line. A road with some farm buildings beside it ran across the plate about three quarters of the way to the trees.

Enemy artillery started again. The iron balls sailed through the air. One struck the ground in front of a neighboring company. It bounced into the ranks, tearing a hole in the formation. Men screamed in pain, screamed with the sound that came with the knowledge of irreversible mutilation.

In the ranks, the men began to talk to each other as they looked out across the landscape of their fate. “Gawd damn it!” one said loudly. “Who’s got it in for us? I guess old Bobby Lee, he don’t have no fu’ther use for us! Whut did we do to deserve this? Somebody’s got it in fer us, fer sure.”

A rabbit ran from cover in front of the regiment, streaking through the ranks into the woods behind the troops. A soldier in the front rank of Thacker’s company sang out. “Run rabbit! I’d run too, if I’s a rabbit!”

“Steady, boys! Steady!” the regimental commander called out.

With a crash of cymbals, the sweet song of fifes, and the barbaric rattle of its copper bottomed drums, a regimental band struck up a tune at the left of the division line.

Thacker could not at first see them. The forest of men was too dense. Heads turned toward the music, then swiveled back to watch for more incoming shells. The invisible band strode forward, turned to the right and marched down the division front toward Thacker’s regiment.

He concentrated on the music.

They passed before him. Their dress contained some elements of the finery of prewar militia elegance. Travel stained long white gauntlets, and a number of black frogged blue jackets were the most obvious relics, but in the main they wore the rough butternut of their army’s true uniform. He tried to remember who had a band with them. He could not.

The drum major raised his mace. The band lengthened its stride, marching to its assigned place at the right of the line..

Thacker focused on a drummer in the rear rank. The mulatto bandsman played his instrument with great spirit, bringing the sticks up to a perfectly horizontal position at the level of his nose after each flourish. On his back was a red and black checked shirt. Across his back was slung a banjo.

The band moved away, out of sight. They played on.

Major General George E. Pickett rode out in front of his division. He brought the horse around to face them.

The band reached its proper place. The music stopped.

Pickett looked at his watch. He raised his head, filling his chest, and ordered the attack. “For your homes! For your honor! For Virginia! The division will advance. Forwaard! March!”

Four thousand, seven hundred officers and men stepped off on their left foot as the band struck up a new tune.

Thacker thought of his wife, thought of the fence he had not finished.

The men were singing. Pickett waited for the refrain.

The general turned in his saddle. “Left Oblique! March!”

The division pivoted on its right foot as one man.

They moved beyond some woods on the left. Thacker saw that there were more troops advancing there. The 45-degree turn would bring them together in one formation.

The Confederate spies stood among the Yankee army and watched the advance come on. The stand of trees was slightly to their right. Just to the front waited a battery of artillery. Fifty feet farther down the modest slope stood a stone pasture wall, three feet high. Union infantry stood elbow to elbow behind it, their regimental and national colors planted among them. More U.S. troops stood in solid lines along the crown of the ridge to either side of the Devereuxs. Claude knew his people should leave, that there was no good reason for personal participation in this tragedy. Nothing could have made him go.

“Why! Why!” Patrick sighed beside him. “There could not be a stronger position than this! Why!“

“What would you have them do?” Frederick Kennedy asked from beside him. The question reflected his confusion at the spectacle before him.

Patrick waved an arm. “This cries out for a night attack.. No one could lose his way here. Mon Dieu!“

Down among the infantry, behind the stone wall, the veteran riflemen stared at the oncoming line.

The distant band continued to play.

A gunner in the battery before them shook his fist at the oncoming enemy, screaming “Remember Fredericksburg” at the Pennsylvania afternoon. You’re right, Claude thought. We shot you to pieces there, just like this. Now it’s our turn, damn you!

There were two major parts to the approaching column of attack. These corresponded to their original dispositions to either side of the triangular patch of trees. All the troops to the left carried the blue flag of the Old Dominion as well as the familiar red battle flag. Those to the right had only the red flags. As the Federal troops watched, the force with the blue flags made another 45-degree marching turn to bring it into perfect alignment with the rest of the column of attack. Artillery fire from the high ground at the southern end of the Federal position continued to tear holes in the alignment of the oncoming troops. These imperfections closed without interruption in the forward movement. The march across the plain before them had the perfection of a garrison review at West Point.

Among the blue riflemen behind the wall, admiration for what they were watching warred with murderous intent. A swarthy, mustachioed First Sergeant of the 69th Pennsylvania Infantry leapt to the top of the wall, waving his kepi at the sky. “Three cheers for the Johnnies!” he yelled at the sky. “Hip! Hip! Hurrah!, Hip! Hip! Hurrah!, Hip!…. Come on Johnnies, we want you!”

Thacker heard the cheering, wondered for a second if it meant anything. The brigade went down into another fold in the ground. In the bottom, they were out of sight of the fearsome position on the ridge before them. The guns to the right continued their terrible work, playing on the straight lines as though their missiles were the balls in a grotesque game of billiards. They marched up out of the bottom, emerging from the depths as though they were new-made men sprung directly from the bowels of the earth itself. As they came up the slope, a collective sigh escaped them. The awful ridge seemed so close now.

The artillery forward gun line lay just ahead of the dip. Dead horses and men were scattered on the field. The cannoneers ceased fire as the infantry passed through the line, masking the fires of the batteries. Officers stood at the hand salute, their faces strained from the trial by fire they had just concluded. The gunners and drivers covered their hearts with their hats. “Good luck, boys!” they said. “We’ll be with you as soon as we limber up! Don’t stop for nuthin’!”

Thacker scrutinized his company commander. His stocky, farmer’s body trudged steadily along. The man had not looked back since Pickett ordered the advance. It was blindingly clear that he would advance to the regiment’s objective alone if they did not follow.

Thacker looked at the two “play-outs” he had been cautioned against.

One of them peered back at him.

Don’t you do it! I don’t much want to kill nobody today, ‘specially you.

Small arms fire began to feel at them. The conical Minie balls whirred by in growing numbers. The infantry on the ridge fired at them by volleys. Men hit with the big lead slugs jerked backwards or spun crazily from the impact. Thacker stepped over a soldier named Herbert Jamison, a friend from home. He had gone down in the front rank and lay moaning, clutching his abdomen. Too bad, too bad, a belly wound. Yer a goner fer sure.. “Close up! God damn it, Morrison! Close up!” Thacker bellowed at his company. My Gawd, Herbert. Who will tend to your ma?

Grasshoppers flew up in clouds from the standing grain as they pushed through it.

The band played on behind them.

They reached a split rail fence beside the road. There was another on the other side. The captain climbed through between the upper and lower rails. Standing in the dust of the road, he turned for the first time to look. A smile creased his homely face at the sight of them. A bullet hit him in the back, throwing his body forward into a fence post. It slid down the rough wood. The post pulled and tore the skin of his face. He lay motionless in the road, his feet pointed at the enemy.

Thacker dropped his rifle, kneeling to pick up the officer’s sword.

The line climbed through the fence on the other side of the road. A group of farm buildings stood in the way. Thacker’s company passed to the right of a red barn. The ridge was two or three hundred yards off now. The enemy infantry fired continuously. White smoke wrapped the hillside, drifting toward the attacking force. He looked left and right. As far as he could see, the troops still pressed forward. There were several thousand men left in the ranks. They now were all across the second fence. It looked like he still had thirty or so men on their feet in the company. The colonel commanding the regiment lay in the shadow of the barn, shot through the head. They halted just past the barn to straighten their alignment. A great, rumbling, growling began to swell from the ranks. Someone in the next company fired his weapon at the ridge. An officer yelled “No!” but his attempt to maintain the tight control needed in the assault was hopeless. The Southern infantry began to shoot at the ridge. Through the smoke, Thacker glimpsed the first rifle shot Union casualties. He watched some of the blue forms pitch back away from the wall.

The brigade started forward down a grassy slope. An officer raised his voice to be heard above the din. “Home, boys! Home! Home is just beyond that hill!” The men began to yell. The wavering shrillness of their battle cry was answered by the deeper sound of Union cheers.

The attack picked up speed through the smoke.

Thacker raised the sword, bellowing, “Come on, Come on!”

They trotted down into the bottom land at the foot of the ridge.

A battery behind the wall fired a volley of canister which ripped a hole in the regiment. Dead and wounded covered the ground to Thacker’s left. Men dropped around him on all sides, kicking and clawing at the grass, victims of the point blank fire of the blue figures behind the wall.

He could now see the enemy despite the smoke. Their shoulders worked methodically in the familiar routine of loading and firing. A stand of colors dominated the section of wall in front of him. The national and regimental flags, stood there together. The regimental color shone a deep green. Upon it was embroidered a golden harp.

The line started uphill. They were taking fire from infantry farther south along the stone wall. Union regiments had crossed the barrier to turn and fire into their right flank.

Something hit him hard in the muscle of the left arm.

Some of the men around him were strangers. Things were getting mixed up. To his left, Thacker saw the Confederate assault roll up the slope. He reached the wall..

They all reached it.

The blue enemy started to draw back with the two flags in their midst.

One of Thacker’s men lunged across the stony barrier to grasp the staff of the national color.

The red and white striped cloth writhed in the smoke and turmoil. A dark featured Yankee with the chevrons of a first- sergeant cried, “No, you don’t, damn you!”, and clubbed the Southerner in the face with his musket butt.

A soldier at Thacker’s side bayoneted the sergeant.

The Rebel line of battle now stood behind the downhill side of the stone wall. Their riflemen loaded and fired with the skill and practice of long habit.

The Union infantry at the crest seemed shaken by the sight of so many of their enemy so close at hand, and protected by the solid stones of the wall. The blue troops began to look over their shoulders at the valley behind.

Thacker thought he had fifteen men left.

Enemy soldiers began to appear on the hilltop in apparent flight from something happening to the left.

He looked in that direction. Blue and red flags surged across the wall in the area beyond the trees.

The battery firing steadily into the ground to Thacker’s left was guarded by the remnants of the infantry pushed back from the wall. Small arms fire cut down gunners and infantrymen alike in the space around the guns. Where’s the Goddam’ artillery? Thacker wondered, looking behind him. There was no one at all behind the Rebel infantry at the wall.

A blonde young major from another regiment appeared at Thacker’s side. He pointed at the battery.

Thacker suddenly saw the truth of it. The battery was the linchpin of the Union line. If it went, the whole center might fall apart.

The battery commander saw the major pointing at him. The man stood hatless in the sun, just behind his cannons. Blood ran down one hanging, useless arm. “1st Section! Action left! Double Canister!” he shouted. In response to his command, two of the guns began to spin on their wheels, manhandled around by brute force.

The blonde major hurdled the wall, sword in hand. “Take the guns! Take the guns!” he screamed at the men behind him.

Thacker stepped back far enough to get a start, and followed him over. What was left of the company went with him.

The two guns spun.

The day stood still as Thacker ran up the slope behind the blonde young man. The smoke seemed less dense. He watched the gun captain of the right-hand piece raise his arm as the men finished loading. Behind him, on the crest of the ridge, the Union infantry brought their weapons up in unison. Thacker’s searching eyes found a little group of men in civilian dress. One of them leaned on crutches.

“Fire!”

Claude Devereux felt his heart stop. Through the smoke he saw the butcher’s ground in front of the two Napoleons. The blonde officer’s corpse lay broken on the grass. One of his hands very nearly touched an ironshod wheel. Behind him, the others were scattered, all the way down to the wall.

Farther up the ridge, beyond the trees, the Rebel attack surged almost to the crest. Human beings stood in ranks and fired at each other at ranges that did not exceed thirty yards. Men howled and rifle bullets whirred across the ground. It was clear that the moment of opportunity for Confederate success had nearly passed.

Devereux had his pocket pistol in hand. He looked about him for a worthwhile target. Major General George Gordon Meade sat his horse 100 yards away. He had just ridden onto the scene. The distance was too long, far too long. Devereux looked at Meade for a time. Glancing around, he spied a Springfield rifle on the ground a few yards away. He gathered himself up spiritually for the act that would surely be his last. He held his brother Patrick by the right arm. Kennedy had him by the left. Devereux thought of the aftermath of what he was about to do. He thought about the vengeance that might be sought. He thought of his youngest brother, and wondered if Jake lay on the field before them. He hesitated.

The shock of the strike of a bullet ran through the three of them. For an instant Claude thought himself hit. The sagging weight on his left drove a dagger of despair into his spirit. They laid Patrick out flat on the ground, a rolled up coat beneath his head.

The fight went on around the trees. It had become strangely unimportant. Bill ripped open the shirt. The wound was in the right breast. A bloody foam surrounded the hole. Pink bubbles formed and broke with each breath. The noise around them built to a crescendo. Abruptly, it was over. The men of Pickett’s and Pettigrew’s divisions drew back in a sudden, collective knowledge of failure. The broken fragments of the column of assault moved back across the field of death. For those farthest forward, there was no possibility of escape. They dropped weapons and raised their hands.

The victorious Federal infantry sat down in place to rejoice in their survival. Their captives sat with them, drained of life by their ordeal. There was much ostentatious sharing of canteens and tobacco with the defeated enemy. The prisoners had little to say. They mostly sat with their backs to their captors and watched the remnant of their comrades in their going. A Confederate colonel, taken prisoner inside the stone wall was brought at his request to the top of the ridge. He looked down into the nearly empty valley on the other side, and wept.”

From “The Butcher’s Cleaver”, a novel

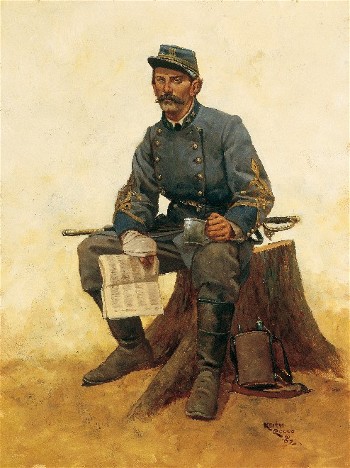

Comment: I thought some of you would enjoy this piece of prose from Colonel Lang. My God, that man could write. When Pat first shared this excerpt in 2020, he added this comment about the above illustration, “This is a family commissioned portrait by Keith Rocco working off an old photo. Major Williamson, 6th Virginia Infantry, lost the left arm later in the war and was head of buildings and grounds at VMI for a long time.”

TTG

My father, Virginia born, called it a not-so-great charge; but he used more colorful 4-letter words. Wasn’t Pickett the ‘Goat’ at West Point, bottom of his class?

And Pickett is disliked here in Washington State for his role in the Pig War on San Juan Island. No KIA in that conflict except for a British pig. But Pickett managed to get the majority of his unit sick and some dead through his lack of establishing field hygiene and sanitation measures. Some died with pneumonia when he had them set up their tents in mud puddles; and others got bloody dysentery from drinking water fouled with sheepshit. So much for looking after the troops. He was probably too busy carousing with the local ladies? And drinking too, didn’t he die of liver cirrhosis?

I believe he was also AWOL at the Battle of Five Forks; losing 3000 casualties and causing Bobby Lee to have to withdraw from defending Richmond.

leith,

The WA state park service has preserved and is renovating the house he live in on SJ Island, they consider it a historical treasure. He is credited with showing considerable spine in the conflict, and had he not, San Juan and several adjacent island would all but certainly belong to Canada today.

https://www.nps.gov/places/pickett-house-officers-quarters.htm

Mark –

Pickett never got it through his thick head to move his troops out of the mud and shit where he bivouacked them. That came from LtCol Silas Casey,Pickett’s superior officer who arrived the following month . And by the way, Casey was the one that brought long range artillery and faced down the Royal Navy. It was Casey and old fuss-&-feathers General Winfield Scott that kept the British Empire from gobbling up the San Juan Archipelago, not Pickett.

Leith,

Can’t agree with that history. Winfield wasn’t there during the incident, he came in later to negotiate the settlement as Pickett, the young captain, was unfit to conduct that. There is a monument naming Pickett as the officer in charge during the incident, google up the park and see the photo, as written in Picketts wiki page. I imagine Lt.Col Casey came in with Winfield and a larger detachment. Pickett only had about 60 men and had faced down a force nearly twice his size…and had ships with cannons. I think he was lucky the Brits on the scene didn’t want a war, because he would’ve been wiped out.

Mark –

There were no British troops on the Island until February or March 1860. Pickett only faced off against sheepherders working for the Hudson Bay Company. His only claim to fame on San Juan was when he reputedly confronted three British warships standing offshore, reputedly in an aggressive manner. Good thing for Pickett and his 68 troops that the British task force commander, Captain Hornsby, declined to start a war because of some quibbling over a dead pig.

LtCol Casey landed a week later with reinforcements and long range cannon. He moved all the troops to higher & dryer ground, out of the cesspit camp that Pickett had established.

When Winfield Scott arrived he mediated with the Brits and together they agreed on joint occupancy, with equal troop strength, until the boundary dispute was resolved. Next he relieved Pickett whose in-your-face attitude had irritated the Brit governor. That happened long before the British troops came ashore. Pickett was sent back by General Harney much later after the Brits set up what was known as the English Camp at Garrison Bay. His attitude changed after the head-shaping by Scott, he did much drinking and a bit of skirt chasing in Victoria with his counterparts.

Leith,

https://www.nps.gov/sajh/learn/historyculture/the-pig-war.htm

The history as the Park Service there recounts that Pickett refused to back down in the face of three British warships for a month and a half, not sheepherders for a week. By preventing that landing he maintained US possession, which was probably key to the subsequent negotiations.

Mark – HistoryLink aka the Online Encyclopedia of Washington State History has a different story:

Pickett arrived San Juan on 26 July.

A single British ship arrived later on 29 July. The other two British warships along with a company of Royal Marines did not arrive until 2 August. The powwow between Pickett and the three Royal Navy captains happened on 3 August.

LtCol Casey arrived on 10 August.

So at the most Pickett “refused to back down in the face of three British warships” only for a week. It had been the HBC that demanded the Royal Marines be landed. But the Brit ship captains awaited orders from their commander Admiral Baynes. He rightfully wanted nothing to do with starting a war for the sole reason of mollifying the HBC corporation because of their hurt feelings over a hog. The Brit Empire at that time had just finished putting down the Sepoy Mutiny in India. They declared the hostilities in India to have formally ended just a few weeks prior. And just a few years before that the Crimean War had ended and there was much war weariness back home in England. Baynes was no fool. He gladly accepted the compromise suggested by Winfield Scott.

The month and a half the Park Service mentions is inaccurate, they need a historian.

https://www.historylink.org/File/5724

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HistoryLink

Great writing! Thanks!

Thank you for sharing the excerpt. At Fkt SSG I was a newly striped E5. All our unit officers had just returned from tours of Nam, and “Maj.” Lang was a young and well regarded officer. I asked how he had fared at VMI. He said. “I was an English major and loved literature”. Yeah right, I thought, he was an English major … sure.

I don’t know how to search the SST comment section but as far as I can remember, the Colonel spoke of Gettysburg so:- “Something was lost that afternoon on Pickett’s ridge.” I think that was because the American Civil War was no ordinary war. No win or lose and come back later for a rematch about it. It decided with irrevocable finality the destiny of a continent.

Lee didn’t talk of Gettysburg as a defeat right after. He’d gone up north to maul the Union army and had done so. Nevertheless it seems to be regarded by many as the turning point in the entire conflict. Meade lost the chance to inflict a full defeat – but Lee the chance to do likewise and the South needed it more. In the Butcher’s Cleaver the disparity between the two sides in munitions and provisions is vividly brought home to the reader. This was, the point was made, a war the South was going to have to win quickly if it was to win at all.

Some 160,000 soldiers fighting over the three day period. I can’t find references for how many were killed, or so seriously injured they couldn’t fight any more.

(The two armies suffered between 46,000 and 51,000 casualties. Union casualties were 23,055 (3,155 killed, 14,531 wounded, 5,369 captured or missing), while Confederate casualties are more difficult to estimate. Many authors have referred to as many as 28,000 Confederate casualties, and Busey and Martin’s more recent 2005 work, Regimental Strengths and Losses at Gettysburg, documents 23,231 (4,708 killed, 12,693 wounded, 5,830 captured or missing). Nearly a third of Lee’s general officers were killed, wounded, or captured. The casualties for both sides during the entire campaign were 57,225.)

https://www.gettysburgpa.gov/history/slideshows/battle-history#:~:text=The%20charge%20was%20repulsed%20by,most%20costly%20in%20US%20history.

The casualties were worse than in another great battle, Waterloo, in which the forces engaged were larger but not by that much. The greater lethality of weapons by the time of the Civil War didn’t, however, warn the European observers that this way of fighting was becoming impracticable: in the succeeding WWI men went up against almost certain death from even more lethal weapons, as if the odds were just as good as when the slow musket fire of the eighteenth century was still the norm.

Waterloo was regarded as a bloodbath by those fighting there but here, if a quick scan of google is to be trusted, the losses were proportionally higher. That without the murderous pursuit that Waterloo had ended with.

I find no account of how the battlefield was cleared afterwards. One hopes it wasn’t as barbaric as the aftermath of that other battle.

https://www.waterlooassociation.org.uk/2018/05/29/the-aftermath/

And for all the carnage, occasional odd moments of humanity, almost of fellowship. These men were more than just machines killing to order.

Corporal Thomas Galwey described a temporary truce which occurred “about the middle of the forenoon” on July 3 in front of the 8th Ohio’s position. It started when numerous Confederate skirmishers shouted, “Don’t fire, Yanks!” Then “a man with his gun slung across his shoulder came out from the tree. Several of our fellows aimed at him but the others checked them, to see what would follow. The man had a canteen in his hand and, when he had come about half-way to us, we saw him (God bless him) kneel down and give a drink to one of our wounded who lay there beyond us. Of course we cheered the Reb, and someone shouted, ‘Bully for you! Johnny!’ Whilst this was going on, we had all risen to our feet. The enemy, too, having ceased fire, were also standing. As soon as the sharpshooter had finished his generous work, he turned around and went back to the tree, and then at the top of his voice shouted, ‘Down Yanks, we’re going to fire.’ And down we lay again.”

https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/picket-line-against-picketts-charge

Yours is a strange trade, TTG. I had occasion recently to read up about Omaha Beach, where the initial carnage was catastrophic. Not many in the first wave survived. And thought again, as here, what is it, that steels men to walk straight into death like that.

EO,

There’s a famous incident similar to your Gettysburg moment of humanity. It’s the story of Sergeant Richard Kirkland, the Angel of Marye’s Heights. It was the first Confederate monument I ever saw firsthand many years ago.

https://sofrep.com/news/battle-of-fredericksburg-and-the-angel-of-maryes-heights/

Very few Warriors are Capable of writing like Pat Lang did .. especially by applying his knowledge experience insight education And Sacred Honor .. The whole Brutal experience Of certain death man on man Combat and cannon balls and grit and Leaders and Lead …The Living Dead .. moving forward Firing Dying Dead Bled out .. Lang Made it all real With a feel for life … in Combat From a Rabbit To a Blond boy To a General ,, Shot in the head .. Pat Lang wrote well .. very well

The Eye of a Warrior .. the Soul if a gifted writer and poet ..Who knew that there is always Lead and Powder and Blood..

In the Ink That writes “Liberty”

“Freedom” Honorable people my regards This 4th of July

JT

Diagram below of how Union Chief of Artillery, BrigGen Henry J Hunt planned and set up his fields of fire from Cemetery Ridge. He had 25 (or 27?) gun batteries zeroed in:

https://www.reddit.com/r/USCivilWar/comments/12go5rd/federal_artillery_fields_of_fire_at_gettysburg/

Poor bastards in Pickett’s Division never had a chance. Enfilade cannon fire from both their left and right flanks. Armistead and his brigade must have had cojones the size of boulders to be able to reach the salient at The Angle and cross over the stone wall while under that intense firestorm of iron.

Here is another pic of artillery placement on day three. Amazingly for once Confederate artillery was not a factor – many overshots (possibly due to firing uphill?) and lack of ammunition (logistics, logistics, logistics as someone here mentioned several posts ago).